What is ethics? Often people assume that it’s something that’s rule-based. “Do this, don’t do that, it doesn’t matter either way, etc.” Certainly, that’s how many ethical systems have been constructed, going all the way back to the Ten Commandments—and even before then! While they can be burdensome, on some level it cannot be denied that we like these rules since they are clear-cut. When someone says, “Do not kill,” there isn’t much doubt about what they mean. Or is there? One might ask, “What about in self-defense? What if it’s hunting for a meal?” And this the the trouble. Rules often lose their relevance when we start living, and encounter situations where we feel there ought to be an exception carved out, or that a certain course of action, while technically in-line, goes against the spirit of a rule.

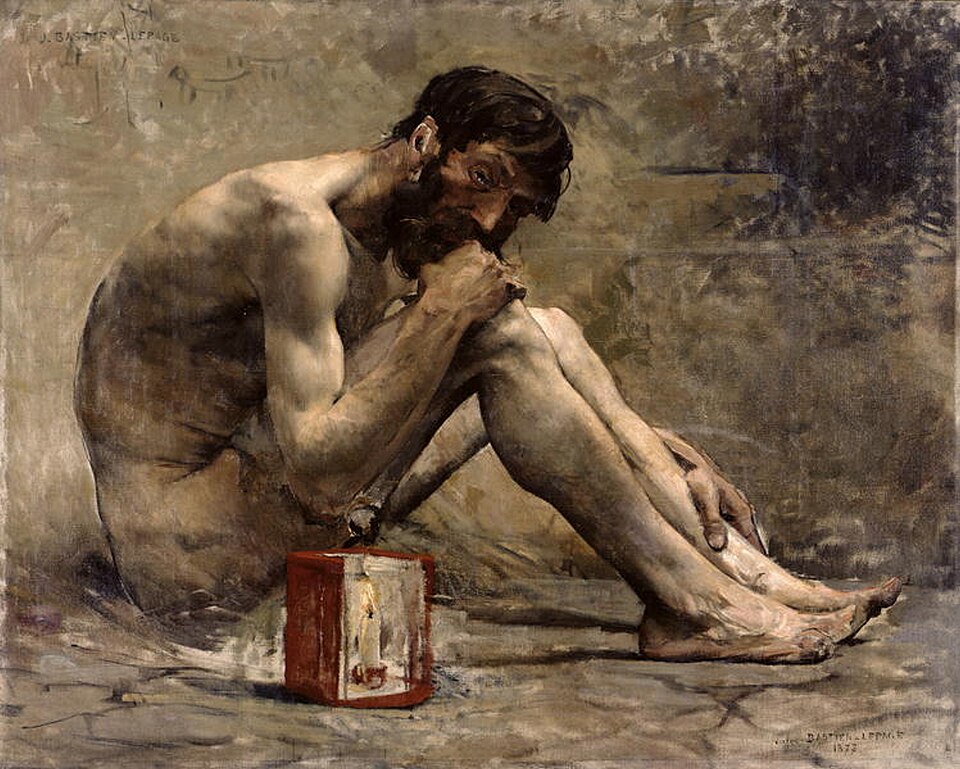

So we developed other systems of morality, too, like virtue ethics. Now we’re not thinking so much about general rules with exceptions but qualities: are you temperate, compassionate, just, courageous, merciful, etc? Generally traditions will enumerate a list of virtues that their adherents should aspire to, but where do these characteristics come from, or are we just pulling them out of thin air? Not only that, but they can be ambiguous or vague. I might assume compassion is however I choose to define it, but where is that line in the sand drawn? Abstract principles, without concreteness, can be spoken of however one wishes. This is not to disparage the concept of virtues, for they can be incredibly useful in describing moral qualities. However, sans personne, they are abstractions without a (literal) foot in reality.

And so we arrive at what I like to think of as the par for the course in moral thinking: moral example incarnate. That is, a good example to follow. Most traditions have one: Jesus, Buddha, Muhammad, Arjuna, Moses, etc. And from these individuals, we arrive at our abstract concepts: the Christ, the Bodhisattva, the Prophet, the Dutiful Warrior, the Liberator. On their own merits, these concepts are wildly unapproachable, but put a face to the name, and you’ll see what that looks like—perhaps what you could look like, too.

We call this the analogical imagination—or at least that’s what it was called in my ethics course—and the idea is that, by studying these moral examples in their own context, we can, by way of analogy, discern how they might live today, and therefore better emulate them. To be sure, this is something quite important for us all to learn. There have been a great many moral women and men in history that we ought to learn from, but notice how, in each case, it was these individuals who preceded our own moral imaginings about them. Each of them had learned and internalized the traditions from whence they came, and then they built on top of it. That is to say, they were prophetic, and broke the mould. They were spirit led, not rule abiding. Or, if you prefer, they had a conscience.

I don’t mean to suggest that whatever one’s conscience tells them to do will be right. It is important to form it properly, learning from wherever wisdom can be found. Be discerning. “You will know them by their fruits.” (Matthew 15:16) Nevertheless, the moral cause of humanity is just as well served by conscientious objection as moral obedience—and who’s to say which is which? I suppose only God would know. Nevertheless, such is the way of moral witness, often ridiculed before its time has come and when it is most dearly needed.

The beautiful is as useful as the useful. Perhaps more so. He said: ‘The beautiful is the light of the truth.’ In the darkest times, it is enough for one just man to exist for the hope of all to remain.

—Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

Leave a Reply